In our 25th year, we are sharing thoughts from people who built the Groundwork legacy and also spotlighting people who are erecting milestones today. Here we talk with Patty Cantrell, who joined Michigan Land Use Institute in 1998 and launched our local food programs, which today make up the largest project team at Groundwork.

Do you recall the first local food project you were involved with here?

Well, it evolved. As a land use organization, we were looking at how to grow communities in ways that keep communities together. We saw growth and development pushing into the countryside and farmers not able to hang onto their land. So one thing we worked on early was trying to stop policies that encouraged people to build outside of town. We did a lot of work to incentivize building inside versus outside of town. But we saw that we needed to change the economic equation, change the market opportunities to create more value in that farmland for farming.

What were the early threads of the solution you came up with?

We saw things happening around the country. We saw things like farmers markets blooming in other states. Michigan didn’t have many farmers markets at that time. We saw that farmers could make more money per acre that way than with commodity crops. Early on, our effort was about direct marketing, cutting out the middleman by connecting farmers to customers at farmers markets and other ways. We also wanted to figure how to build new market infrastructure, like distribution, that could help grow the local and regional food sector with wholesale marketing to schools, grocery stores, and such.

What was the action that grew from that?

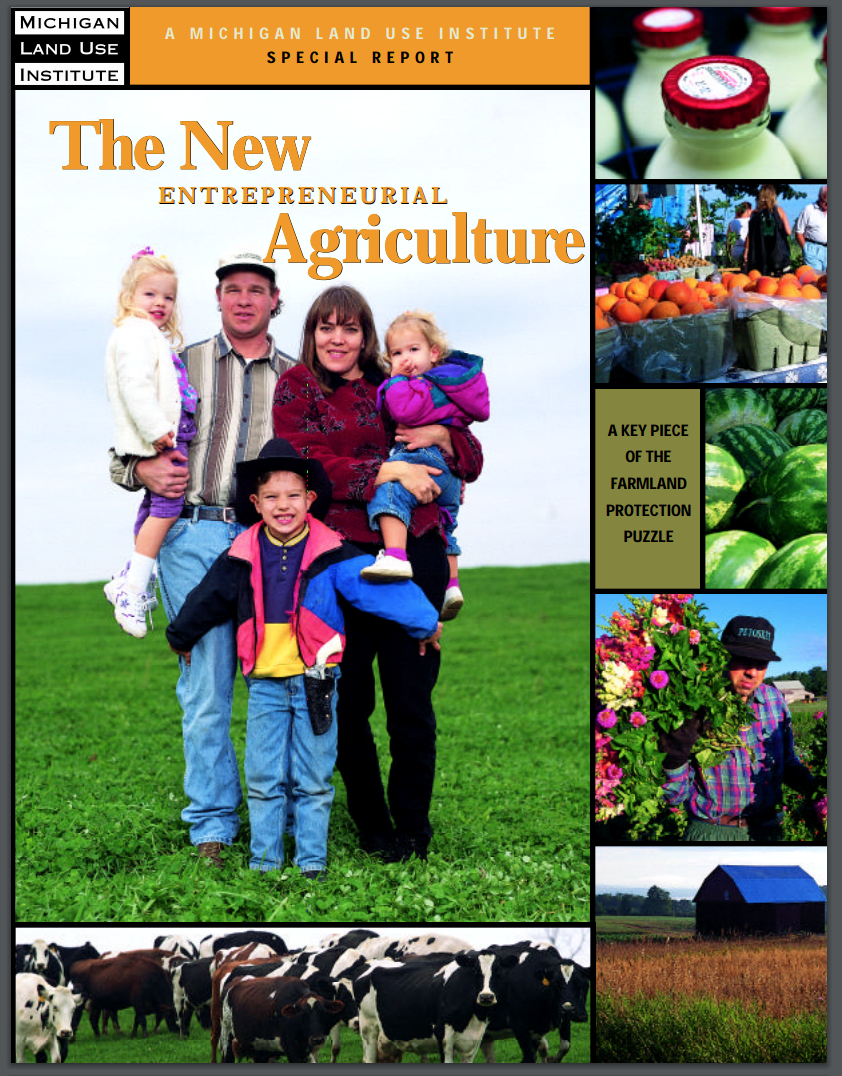

The first thing we did was lay out that opportunity in a report, The New Entrepreneurial Agriculture: A Key Piece of the Farmland Protection Puzzle. We contrasted commodity farming—taking crops to the global market with little focus on the consumer—and a kind of entrepreneurial farming that did focus on the consumer, filling niches, going after opportunities. We suggested the region could use a lot more entrepreneurial agriculture in the mix to keep farmland and farm families going.

What were some of the sources of inspiration for that approach?

A main one was agricultural economist John Ikerd. He was pointing out that small farming is real farming. At the time, others did not think that. He was doing research showing that smaller farmers could net more money and have more fun getting closer to the end consumer. We were also inspired by local people like Wendy Wieland from the Petoskey area. She was doing something new: Including small farms as small businesses in economic development. People didn’t think of them that way. We took up this banner and partnered early on with the chamber of commerce. They recognized that farms are a really important part of the local economy and were strong supporters of the effort, even beyond the report.

So the mission was to kind of create a market system that resembled the system that commodity farming displaced, a system where a lot of food was sold locally.

Yes. We knew that to get this rolling we had to get people connected; many had no idea that the place down the road has great blueberries. We just had to figure out how to connect them, and that was how the Taste the Local Difference directory of farms came to be.

What other partners jumped in on that effort?

I have to say that one of the most gratifying things for me is how the broader agricultural community eventually embraced Taste the Local Difference and joined in building farm-to-school and the Northwest Michigan Food and Farming Network. When we started TLD we were still the environmental organization that many thought of as standing in the way.

But this program delivered. It didn’t solve every farmer’s economic challenges, but it helped. We heard from farmers that it helped people diversify and build customers. And that’s valuable because farming is not a business that will grow to be traded publicly. It is a lifestyle. It is land-connected. It is different that way.

Were there special conditions that existed here 20 years ago that helped get the idea off the ground?

All the elements for building the business of local food were here. We had Michigan State University Extension people talking about this, and others. And we had a good mix of vegetables and fruits and tourists to buy them. Many areas don’t have that. What we brought was a “let’s do this” attitude. We had an entrepreneurial energy ourselves, and the time was right and the place was right. We brought the advocacy voice and the entrepreneurship to start the guide, but we did not have funding at the time. We just said let’s make this happen and go from there! And Diane Conners came along right then to put the first directory together. We lit the match for sure, but the kindling was already there.

I’ve heard you say “so much of environmentalism is about stopping something bad, but I wanted to be part of starting something good.” That’s a powerful idea that is still a big part of Groundwork.

We know we do want to fight back against the bad, but also important is the emergence of the new and better solution. We saw there was interest and energy in local food. We thought about how we could focus that, how we could help it emerge. The institute has had to stand up and speak out against what was bad, and that is important. But we have also helped the new emerge and this is powerful together.

The entrepreneurial agriculture report sounds like a big lift—what kind of research went into that?

I did a lot of reporting for that report. I talked to everybody I could. I went to the East Coast and talked to people who were doing direct selling. I talked with farmers in Michigan about their efforts to do that. I visited George and Sally Shetler, pioneers in this. Long before we published the local food guide, we were learning about and explaining and packaging up what this is about.

Talk about the farmland preservation piece of this. How important was that to this movement?

When you talk about farmland preservation, it is directly related to the farm economy equation. We worked to help people understand how that connects to us, how the local food movement goes beyond just going to the market and buying a carrot. Back then, even people in land preservation were pretty disconnected from farming and the people working the land. But we knew we had to think about the people on that land and reveal how it relates to each one of us, and how that connection beyond the dollar flow is powerful and important.

Can you recall what it was like working at the organization back then?

It was the best working place. Because the deal is, we were able to sit down and hash out things in a loving and intense way. We would have arguments, but we all loved each other very much and were able to come up with some new things and bold things because we could relate to one another and loved the place where we were working. That is a great model of an organization, and I take it with me where I go.

You now run a nonprofit. Can you tell us a little about it?

We are into our third year starting a rural community development organization called New Growth. We now have nine people on our team. It’s in rural Missouri. I think of our work like I think of soil. If you have poor soil you have to start building from the organic sense, new growth from deep roots. We have a lot of assets but we have to cultivate that so the soil can have growth here.